A Brief History of Dog Training

Dogs have surely been trained countless different ways throughout various places around the world for thousands of years, but modern dog training ideologies really begin with the behavioral scientists Ivan Pavlov and B.F. Skinner.

Pavlov's Classical Conditioning

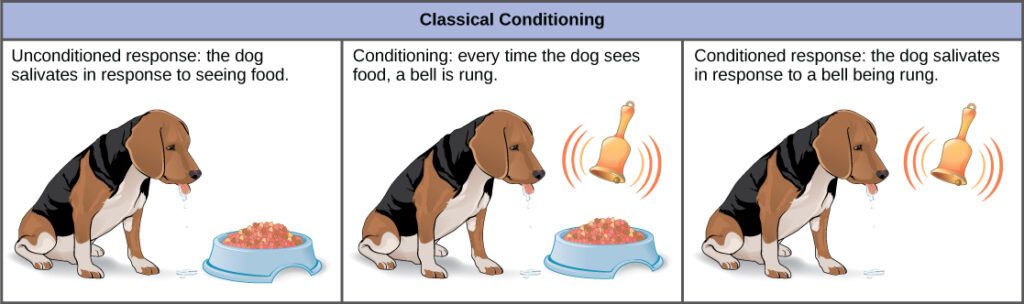

In the 1890s, Pavlov was performing experiments with dogs to better understand animal (and therefore human) behavior. He noticed that the dogs began to salivate at feeding time before they even received food, possibly because of the sound of the food cart, possibly by the presence of the humans bringing the food. He eliminated both factors by setting up an automatic feeding system where a bell would ring shortly before the food was dispensed. After a few repetitions of this pattern (bell, then food) he noticed that the dogs would exhibit physiological behaviors appropriate for having food as soon as the bell rang—namely, salivation. Once a dog became conditioned this way, it would salivate every time the bell rang, even if no food followed several times in a row. If the bell and the food happened at the same time, this response would never be generated. If the bell came after, it would never happen either. The bell had to precede the reward by a short period.

This, he termed, “Classical Conditioning”. The stimulus that predicts a reward (the bell in this case) he called the “Conditioned Reinforcer”, and the food (in this case) he termed the “Primary Reinforcer”. We commonly call the conditioned reinforcer the “marker” because we can use it to mark a behavior, and the primary reinforcer we usually call the “reward”. You see this used in dog training all the time. The trainer says “sit”. Dog sits. Trainer says “Yes!” or clicks a clicker (the marker) at the exact moment the dog’s butt touches the ground. He then reaches into the treat bag and gives the dog a treat (the reward).

Skinner's Operant Conditioning

About 40 years later, another behavioral scientist, B.F. Skinner, performing experiments on rats and pigeons, came up with another theory of behavior call “Operant Conditioning”. This basically says that our behaviors are primarily shaped by the outside environment. How likely I am to perform a certain behavior depends on what happens to me when I do it. If I’m “punished” by the environment for putting my hand on a hot stove, I’m less likely to do it again. If I get a financial bonus (a reinforcement) for working extra hard, I’m more likely to work extra hard again.

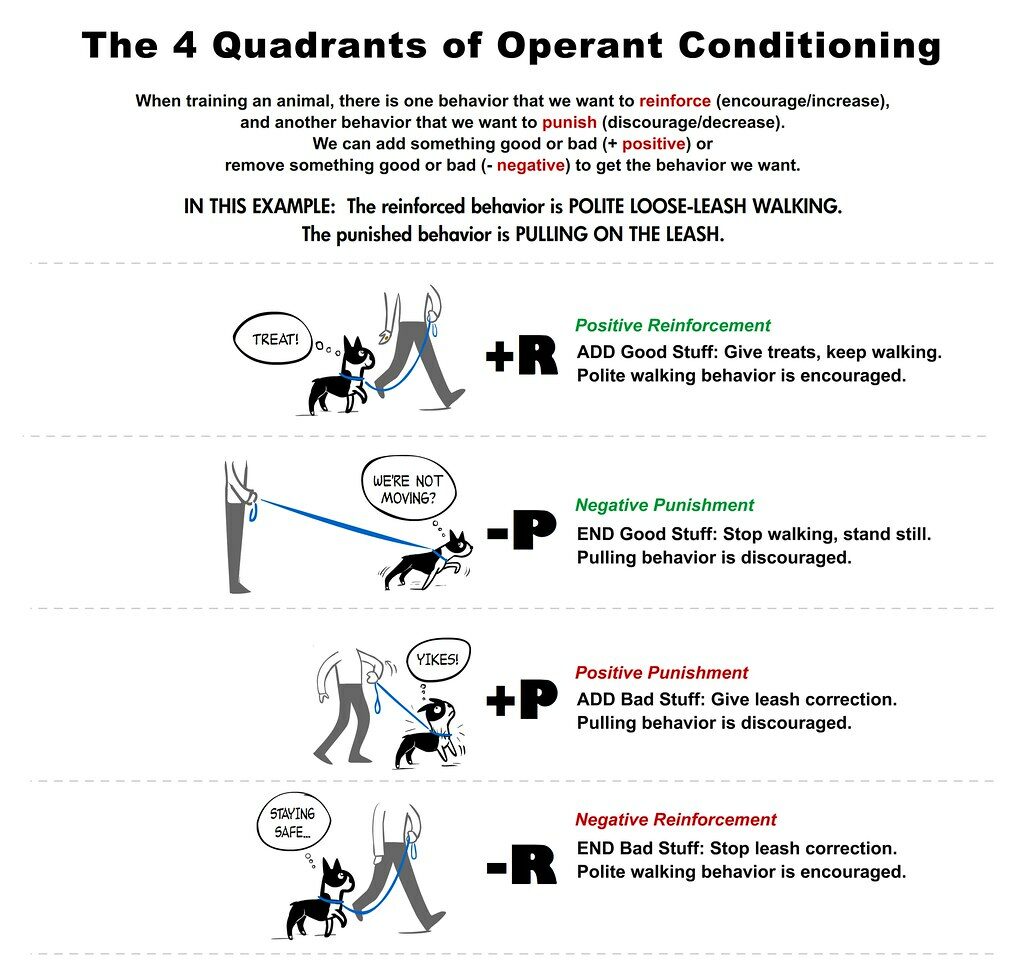

Skinner uses terms a bit differently than we might: “positive” (adding something), “negative” (removing something), “reinforcement” (something that makes a behavior more likely to happen again), and “punishment” (something that reduces the likelihood of a behavior recurring). Mixed and matched together these create the “Operant Conditioning Quadrants”. They consist of: Positive Reinforcement—Adding something to make a behavior more likely (like giving a dog a treat for sitting). Positive Punishment—Adding something to reduce the chances of a behavior recurring (like popping a prong collar when the dog tries to pull). Negative Reinforcement—Removing something to make a behavior more likely (applying steady downward pressure on a leash, then letting it go slack once the dog Down’s). Negative Punishment—Removing something to reduce the chances a behavior will recur (such as when you stop playing with your dog because she got too excited and nipped you).

About 40 years later, another behavioral scientist, B.F. Skinner, performing experiments on rats and pigeons, came up with another theory of behavior call “Operant Conditioning”. This basically says that our behaviors are primarily shaped by the outside environment. How likely I am to perform a certain behavior depends on what happens to me when I do it. If I’m “punished” by the environment for putting my hand on a hot stove, I’m less likely to do it again. If I get a financial bonus (a reinforcement) for working extra hard, I’m more likely to work extra hard again.

Skinner uses terms a bit differently than we might: “positive” (adding something), “negative” (removing something), “reinforcement” (something that makes a behavior more likely to happen again), and “punishment” (something that reduces the likelihood of a behavior recurring). Mixed and matched together these create the “Operant Conditioning Quadrants”. They consist of: Positive Reinforcement—Adding something to make a behavior more likely (like giving a dog a treat for sitting). Positive Punishment—Adding something to reduce the chances of a behavior recurring (like popping a prong collar when the dog tries to pull). Negative Reinforcement—Removing something to make a behavior more likely (applying steady downward pressure on a leash, then letting it go slack once the dog Down’s). Negative Punishment—Removing something to reduce the chances a behavior will recur (such as when you stop playing with your dog because she got too excited and nipped you).

Dog Training Today

There’s a phrase fluttering around the dog training world—“Science-Based Dog Training”. As I mentioned, modern dog training is primarily rooted in the above behavioral science discoveries, and this is the science referred to in a “science-based” dog training.

Positive Reinforcement trainers focus on positive reinforcement and negative punishment—giving out rewards to make behaviors more likely, and taking away things the dog wants to stop unwanted behaviors. Traditional trainers generally use a bit of all but are very reliant on positive punishment and negative reinforcement—so they might stim a dog with and e-collar when it does the wrong thing or hold a continuous stim until it gets into the right position.

Nobody really calls themselves traditional trainers anymore, but if the training is based around compulsion—basically trying to set up the scenario so that the dog disobeys and then punishing him for doing so until he stops disobeying entirely—this is essentially what traditional training is, and it’s how dogs primarily used to be trained. Everyone else calls themselves “balanced” trainers, meaning they openly use all four quadrants of Skinner’s Operant Conditioning theory.

In truth, everyone uses punishment to some degree, whether they’re aware of it or not. If we made a scatter chart that placed trainers on it based on their willingness to use punishment, you’d have the positive reinforcement trainers bunched up on one side, the traditional trainers on the other, and all the “balanced” trainers scattered more or less evenly throughout.

Who's Right?

There are dogs who can do amazing things who’ve received positive reinforcement only, and dogs who’ve been saved by last-chance traditional training who didn’t benefit at all from previous positive reinforcement trainers. Positive reinforcement is generally much more time consuming and requires more creative and experienced trainers for difficult cases, and traditional training usually gives quick results but often at the price of unintended neurotic behaviors. Positive reinforcement trainers are stuck repairing trauma caused by traditional trainers, and traditional trainers take on highly aggressive dogs whose aggression has sometimes only intensified from positive reinforcement strategies, and save them from behavioral euthanasia.

The best dog trainers in the world are not all balanced or all positive reinforcement trainers, they’re all over the scatter chart. I suspect that in another decade or so we’ll see Skinner’s quadrants as much less central to our dog training methodologies, which due to our unique relationship with dogs makes this training different than any other animal training. Operant Conditioning applies to human behavior just the same as for animals, yet educators and coaches do not classify themselves the same way or develop their methods based on these quadrants as dog trainers do. Dogs aren’t people, but our relationship with them is categorically different than it is with the rest of the animal kingdom. Skinner and Pavlov were brilliant and contributed greatly to behavioral science, but they could also be quite cruel and certainly did not understand the relationship we have with dogs today, 80 years later. Classical and Classical conditioning are there, but they are not all that is there.

So let’s go play with some dogs.